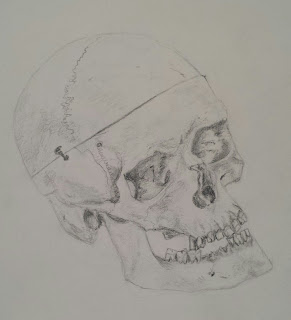

These two sisters, the only children in their family, were always close. They both worked all their lives, and were extremely competent and very kind. My great-aunt never married; her fiancé had gone off to fight in the Spanish-American war, but died during an outbreak of yellow fever in Florida before he ever got to Cuba. But, she lived with a cousin for many years. When my parents finally cleaned out the apartment after my great aunt died, one of the things they found in the attic was a skull that must have once been used for teaching anatomy. No one had any clue how it ended up in that attic. My parents have displayed in their living room for most of my life. My mother's theory, after years of living with it, is that this is the skull of a poor man who was suffering from an abscessed tooth, and he shot himself in the head because he couldn't stand the pain. Here's a sketch.

|

| Sketch by A Buchanan |

My grandmother married and had one child, my father. My grandparents, my great-aunt and her cousin all lived perhaps half an hour from us, in the town where my father had grown up, and my grandfather drove them all to visit us on Sunday afternoons. He loved driving -- he enjoyed taking my sisters and me for drives in the country. What I remember most about these drives was the overwhelming odor of his strong cigars. (He used to enjoy shooting woodchucks, too, happy to be doing farmers such a favor. I remember going with him and my grandmother once on such an outing, but I refused to take a shot, which disappointed him. He would steady his gun on the roof of the car, aim and shoot. He draped the one woodchuck he killed the day I was with him over the gate into the field he'd shot it in, so that the farmer would take note. One Sunday when they came to visit, there was a bullet hole in the roof of the car, over the passenger side -- I don't remember that that was ever explained.)

Dementia does unpredictable things to people. My great-aunt -- Aunt, we called her, as my father had -- was always cheerful and sweet, if a bit confused. Every morning she would ask where she was, but she was still able to play cribbage with us, she loved having us comb her long thin hair, past grey, now yellowed, and pin it into a bun. I don't remember that she ever fussed about anything.

My grandmother, on the other hand, was distraught with worry from the moment she woke, to the moment she went to bed, and probably long after that. She would sit at the kitchen table all day every day, every few minutes asking the same worried questions in the same frantic way. She was miserable. Occasionally she was able to access a part of her brain that reminded her that she was confused, and that made things even worse.

Apart from being two different versions of the same heart wrenching story that could be told by so many people, this raises several questions. Was this two sisters with very different forms of the same disease? Or, did they have two different diseases?

And, did the fact that both his mother and his aunt had dementia mean that my father was at higher risk of dementia himself? Apparently not, as he is now in his late 80's, still very active, very engaged, mentally and even physically. In turn, does this mean that my sisters and I don't have to worry about dementia ourselves?

Or is it secular trends in Alzheimer's disease that we should pay attention to?

One measure of a condition's impact is its prevalence. That is the fraction of the population at a given point in time that is affected. A recent BBC Radio 4 program, More or Less, discussed changes in Alzheimer's prevalence over time, after a paper reporting (among many other things) decreased prevalence of dementia in the UK was published in The Lancet ("Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990–2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition," Murray et al.). According to the study, prevalence of dementia in British people over age 65 has declined by more than 20% in the last 20 years; it's currently about 7 percent of that segment of the population.

This is in striking contrast to a recent report in the UK that estimates that 1/3 -- 33%!-- of the British children born in 2015 will have dementia in later life. Tim Harford, presenter of More or Less, pointed out, though, that it's odd that this number was taken seriously by anyone, given that it is equivalent to thinking that predictions made 100 years ago, when AIDS wasn't known, antibiotics not yet discovered, and so on, would have any credibility. And, the 1/3 estimate was based on 20 year old data. (A quick check of prevalence of dementia in the UK is a bit confusing -- many sites caution that the number of people with Alzheimer's disease is rising rapidly. It's an Alzheimer's time bomb, they warn. But, given that the population is both aging and increasing, this isn't, in itself, a surprise, or very meaningful in relation to individual biological risk because, again, it's the fraction of the population that is affected that is the significant statistic. To be clearer, if more people live longer, even the same age-specific risk of getting a disease will lead to more people with the disease, that is, higher prevalence in the population. Of course, the number of affected individuals is relevant to the health care burden.)

How predictable is dementia?

Carol Brayne, one of hundreds of authors on the Lancet report and interviewed for More or Less, speculates that the reported fall in prevalence has to do with changes in 'vascular health', as incidence of heart attacks and stroke have fallen as well. She suggests that it seems as though the things we have been doing in western countries to prevent cardiovascular disease have been working.

But of course this assumes we know the cause of dementia, and that it's in some sense a cardiovascular disease. But, we don't understand the cause nearly well enough to say this, and in fact, like most chronic diseases, dementia is many different conditions, with many different causes.

The genetic causal factors related to Alzheimer's disease include mutations in a few genes, but these account for only a fraction of cases. Mutations in the two presenillin genes can lead to early onset Alzheimer's. The most commonly discussed genetic risk factor has to do with the E4 allele in the ApoE gene, whose physiology is related to fat transport in the blood. It seems to be associated with the development of plaque in brains of people with late onset (60s and over) Alzheimer's, but the association is complex, people without the E4 allele also develop plaque, and people with plaque may not have dementia, and the causal mechanisms are unclear. Risk seems to depend on whether one carries one or two copies of the E4 allele, and seems to be higher for women than for men, and is apparently affected by environmental factors, but it does seem to raise risk from something like 10-15% in people over 80 to 30-50%.

What this means, even if the statistics were reliable, the risk estimates stable, and environmental contributions minimal, is that it is obvious that even having two copies of the risk allele is not a guarantee of Alzheimer's disease. And, in some populations having two copies isn't associated with Alzheimer's at all (Nigeria, e.g.). In addition, while the association with increased risk has long been described, the physiology is still not understood. GWAS have reported other genetic risk factors, but not nearly as consistently as ApoE4, nor as strong.

The reported decline in dementia prevalence is not new; we blogged in 2013 about dramatically decreasing rates in the UK, as well as in Denmark, as reported by Gina Kolata then. So, how can it be declining rapidly, but the strongest risk factor we know of is genetic -- and the frequency of this variant is not changing enough to even begin to account for the data? Or, is Carol Brayne right that dementia is a vascular disease, and vascular diseases are on the decline, so Alzheimer's is, too?

Indeed, even the definition of whether you 'have' Alzheimer's or not is changeable and not precise, and researchers don't even agree on what an Alzheimer's brain looks like. A good discussion of these various factors, including social and economic aspects and the history of studies of Alzheimer's, is a book The Alzheimer Conundrum, by Margaret Lock, a fine medical anthropologist at McGill in Canada (and friend of ours).

Can Alzheimer's be prevented?

The causes of Alzheimer's disease are so poorly understood that it's said that the best prevention is to exercise, quit smoking and maintain a social life. Very generic advice that could apply to a lot of things! If we don't know what causes it, and there are probably environmental risk factors, which we don't really understand, relevant past environmental agents are unknown, future environments impossible to predict, and genetic risk factors not good predictors, then we certainly don't know how to predict population prevalence rates, not to mention who is most likely to develop the disease. (NB: this is pertinent to late-onset dementia; early-onset is more likely to have a genetic cause, and is thus more likely to be predictable.)

Given the experience of two generations in my family, should I or shouldn't I worry about developing dementia? If my grandmother and great-aunt had the ApoE4 risk allele, my father may or may not, and my sisters and I may or may not. If they did and my father does, it's a good example of an allele with "incomplete penetrance," for which either genetic background or environmental risk factors or both are also necessary. Which makes predicting dementia difficult, whether or not we were to have the risk allele. If they didn't have it, something else caused their dementia, and we have no idea what that was. Indeed, they were both social, never smoked, and walked to work for decades.

To me, as to most people, dementia is frightening. But, obviously, my family history is useless in terms of determining my risk -- my grandmother had it, my father doesn't.

Still, every time I forget someone's name, I think of my grandmother.

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder